COP26: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Glasgow

Carbon Brief Staff

11.15.21Carbon Brief Staff

15.11.2021 | 4:30pmThe UN climate conference, COP26, finally took place in Glasgow, with expectations and tensions running high after a year-long delay due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

The two-week meeting was seen as a critical moment for commitments and action after richer nations had failed to raise the $100bn annual climate funding they had promised to vulnerable countries and the gap to staying below 1.5C loomed large.

As record-breaking numbers of delegates gathered in the Scottish city, they were joined by world leaders inside the vast venue beside the Clyde river and huge crowds of protesters outside.

Under tight Covid restrictions that limited access for observers, negotiators finally brought discussions around the Paris Agreement “rulebook” to a close, including regulations around carbon markets and regular reporting of climate data by all countries.

Meanwhile, the UK presidency of the COP had set itself the ambitious task of “keeping 1.5C alive”, referring to the stretch target of the Paris Agreement that will limit some of the most destructive impacts of climate change, if achieved.

Whether they succeeded or not is up for debate, but the “Glasgow Climate Pact” that emerged from the summit was welcomed by many for its commitment to doubling adaptation finance and requesting countries to present more ambitious climate pledges next year.

Others were disappointed that this COP once again failed to provide vulnerable nations with the money to rebuild and respond to the unavoidable impacts of climate change.

Much was also made of a last-minute intervention from the Indian environment minister Bhupender Yadav that saw language around moving beyond coal weakened in the final text. The call to “phase down” unabated coal use is, nevertheless, unprecedented in the UN climate process.

Here, Carbon Brief provides an in-depth summary of all the key outcomes in Glasgow – both inside and outside the COP…

- Overview of the COP26 summit

- Formal negotiations

- Around the COP

- Road to COP27

Overview of the COP26 summit

In the months before COP26, people on every continent had felt the visceral impacts of a changing climate at just 1.1C of global warming, being hit by floods, wildfires, storms or heatwaves.

The talks had also suffered under the cloud of Covid, which first delayed them for a year and then, for months, placed a question mark over them taking place at all, let alone in person.

Continuing restrictions due to Covid had made it impossible for some to reach Glasgow, while observers faced many challenges accessing the negotiations. (See: Covid, queues and access.)

The economic impacts of the pandemic also cast a shadow, having reduced incomes, cut into government budgets and pushed many into poverty, particularly in developing countries.

This year’s COP – the fifth since COP21 in Paris – were seen as particularly important, with countries due to have brought stronger pledges under the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet” mechanism.

Some 151 countries had responded by submitting new or updated “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs) to the UN – including China, just days before COP26 started.

Others, including Algeria, Iran and India, had stopped short. India announced new targets at COP26, but has so far refused to formally submit them to the UN. (See: Leaders summit speeches and new NDCs.)

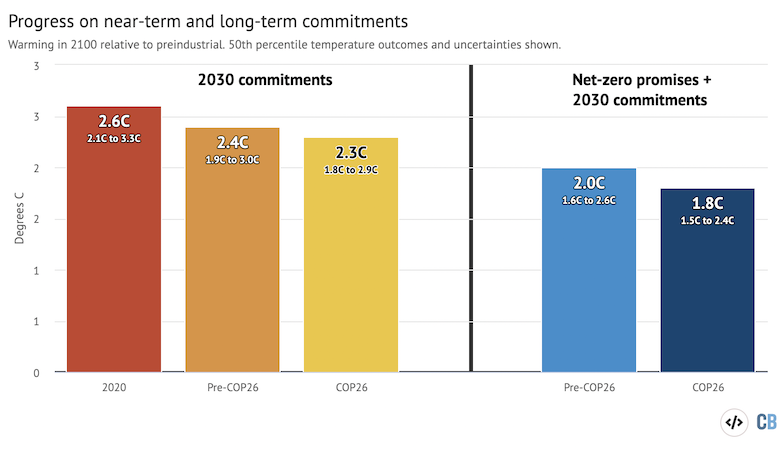

While the new pledges had increased ambition – shaving some 0.2C off warming, if fully implemented – the UNEP “gap report” just before COP26 had once again exposed the gulf that remains, if the world is to stay below 1.5C. (See: Do new climate pledges “keep 1.5C alive”?)

Coming into the talks, the UK COP26 presidency had set high expectations, calling for the summit to “keep 1.5C alive”, with a focus on action to address “coal, cars, cash and trees”.

We must keep the goal of 1.5 degrees Celsius warming alive.

— António Guterres (@antonioguterres) November 1, 2021

This requires greater action on mitigation and immediate concrete steps to reduce global emissions by 45 per cent by 2030.

We need maximum ambition – from all countries on all fronts – to make #COP26 a success. pic.twitter.com/mb9d8djQS6

The 1.5C ambition had been squeezed into the Paris Agreement in “the last hour of the last day” of COP21, according to Laurence Tubiana, head of the European Climate Foundation (which funds Carbon Brief) and a key architect of the deal, speaking at a COP26 press conference.

Yet since 2015, the severe additional impacts of warming at 2C, rather than the lower Paris limit, had become increasingly clear – not least via the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on 1.5C, published in 2018.

In the first part of its sixth assessment report, published in August and described as “code red for humanity”, the IPCC had shown that the world is likely to hit 1.5C by the early 2030s.

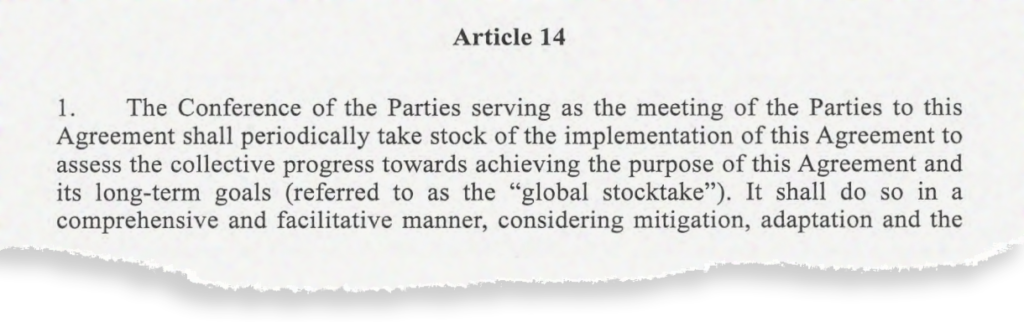

Against this backdrop, negotiators were due to arrive in Glasgow to adopt a series of dense, technical decisions to finalise the Paris “rulebook”, including new emissions reporting rules for all countries from 2024 and the Article 6 carbon markets. (See: Formal negotiations.)

Despite also agreeing processes towards a new global goal on adaptation, a new climate finance goal from 2025 and loss and damage finance, the talks could easily have been seen as an irrelevance against what the US and China jointly called the “climate crisis”.

COP26 attempted to respond to the glaring disconnect between the jargon-filled negotiating halls and the increasingly alarmed populace in the outside world in two ways.

First, with a barrage of new country pledges announced at a “leaders summit” at the start of COP26, plus sectoral deals covering coal, deforestation and methane, among other things. (See: Around the COP.)

These pledges, if fully implemented, would tweak the curve of emissions and shave another 0.1C off the increase in temperatures that had been expected.

“The meaning of COP is shifting,” said Naoyuki Yamagishi, energy and climate director for WWF Japan. He told Carbon Brief: “It is no longer just about formal decisions. We’re seeing a changing phase of the Paris Agreement from rulemaking to implementation.”

Second, COP26 introduced a broad, political “cover decision” – the “Glasgow Climate Pact” – calling for renewed efforts to raise ambition on cutting emissions, climate finance, adaptation and the loss and damage already being caused by warming.

The pact “requests” countries to raise their ambition again next year and creates a “Glasgow Dialogue” on funding for loss and damage, as well as pledging to double adaptation finance.

It is also the first-ever COP decision to explicitly target action against fossil fuels, calling for a “phasedown of unabated coal” and “phase-out” of “inefficient” fossil-fuel subsidies.

The UK COP26 presidency had no formal mandate for this, but after frenzied last-minute diplomatic wrangling around a slight weakening of the language on coal, it was eventually adopted by consensus. (See: Glasgow Climate Pact.)

📢 BREAKING: The #COP26 Glasgow Climate Pact has been agreed.

— COP26 (@COP26) November 13, 2021

It has kept 1.5 degrees alive.

But, it will only survive if promises are kept and commitments translate into rapid action.#TogetherForOurPlanet pic.twitter.com/PtplIsVPCF

While past cover decisions were usually the result of a specific mandate, the “Chile Madrid Time for Action” adopted at COP25 offered a precedent for the Glasgow text, explained Paul Watkinson, former chair of one of the subsidiary bodies of the UN climate convention (UNFCCC) and chief negotiator for France during the COP21 summit in Paris.

Watkinson told Carbon Brief:

“Madrid was the first time we had a decision that was purely a political overview decision, including points that needed a home which did not exist elsewhere. The COP26 decision takes that a lot further with a long list and a wide scope. It was a risky move, but I think it has worked.”

The Glasgow talks followed the 2019 COP25 summit in Madrid, where many issues had not been agreed, with the meeting instead applying “Rule 16” of the UN climate process.

This rule had been used to kick matters down the road to Glasgow, including the Paris transparency rules, Article 6 and “common timeframes” for climate pledges.

The interactive table below, compiled by Carbon Brief, shows why it had been so hard to make progress. It illustrates how the positions of key negotiating alliances, on each issue at the talks, create a “four-dimensional spaghetti” of competing priorities.

Who wanted what at COP26. Table by Tom Prater for Carbon Brief.

Since Madrid in 2019, negotiators had met formally only once, at a virtual summit in June 2021, where little progress was made and discussions were marred by technical difficulties.

The UK presidency had also held a series of informal meetings and ministerials throughout 2021, in an attempt to move forward on the knottiest issues heading to Glasgow.

Once COP26 opened, negotiations got off to a surprisingly smooth start, as the agenda was formally adopted without the sort of “process fight” that has marred previous talks.

By the middle Saturday, the technical talks under the “subsidiary bodies” of the UNFCCC were supposed to have passed the baton to the political phase of the summit.

In well-worn tradition, however, progress had been slow and COP president Alok Sharma announced a three-track approach for the second week, with continued technical talks, ministerial discussions in key areas and ongoing presidency consultations on the cover text.

Yesterday I convened our Ministerial Co-facilitators to discuss Article 6, Common Time Frames, transparency, adaptation, mitigation and keeping 1.5 in reach, loss & damage and finance

— Alok Sharma (@AlokSharma_RDG) November 9, 2021

I urge all Parties to work constructively with the Co-facilitators to reach consensus #COP26 pic.twitter.com/Xcclbc6K8J

After two weeks of increasingly frantic negotiations, the gavel came down at 11.27pm on Saturday 13 November, making it the sixth longest COP on record.

As the Paris ratchet clunked forward, before and during the summit, with new 2030 promises amounting to 0.3C less warming if met, ambition remained well short of 1.5C.

Vulnerable countries also left bitterly disappointed that their calls for a Glasgow “Loss and Damage Facility” were blocked by the US and EU. (See: Loss and Damage.)

Yet despite question marks hanging over the COP26 pledges – and the processes kicked off by the Glasgow Pact – the outcome was widely seen as a step forward.

Formal negotiations

At the very heart of COP26 – and the key reason why the event was even taking place – were the formal negotiations between parties.

Each year at COPs, there are negotiations about a wide variety of issues, which are all overseen and administered by the UNFCCC.

At Glasgow, there were the various agenda items of the three main “governing bodies” – COP26 (the “supreme body of the Convention”), CMP16 (serving the Kyoto protocol) and CMA3 (serving the Paris Agreement) – as well as the ever-present work of the two main “subsidiary bodies”, known as SBSTA and SBI, whose more technical work programme, as ever, dominated the first week.

All of the formal outcome texts from COP26 have now been placed onto a single webpage by the UNFCCC – which is both useful and also highlights the complexity of the negotiations.

At COP26, Carbon Brief asked party delegates, observers, scientists and campaigners for the one key outcome they would like to see from the meeting in Glasgow. A number of them focused on topics being discussed by negotiators.

Video by Tom Prater, Joe Goodman and Ayesha Tandon for Carbon Brief.

Below, Carbon Brief has separated the negotiations into the key topics…

Glasgow Climate Pact

The surprise package at COP26 was the adoption of a “Glasgow Climate Pact”, an unprecedented, lengthy and wide-ranging political decision towards a more ambitious climate response.

This text “requests” that countries “revisit and strengthen” their climate pledges by the end of 2022, calls for a “phasedown” of coal and sets up processes towards delivering a global goal on adaptation, higher levels of climate finance and finance for loss and damage.

Although the text left many disappointed over a lack of “balance” between the strength of language and action on emissions cuts, relative to finance or loss and damage, the fact that it was agreed at all is a relative novelty for the COP process.

As noted above, there was no mandate for the UK presidency to push through this decision, which did not appear on the agenda for any of the formal proceedings.

The Glasgow pact is much longer than the equivalent documents agreed in the “Chile Madrid Time for Action” cover decisions at COP25 in 2019, which ran to a total of just seven pages and largely reiterated wording from the Paris Agreement.

The Glasgow text – which is actually split across three documents – weighs in at 11 pages for the cover decision to the Paris Agreement (1/CMA.3), plus another eight pages for the decision under the UN climate convention (1/CP.26) and one more for that under the Kyoto Protocol (1/CMP.16).

Moreover, there is a marked shift in the language – and specificity – that countries were collectively willing to sign off in Glasgow, compared with earlier summits.

Just three years ago at COP24 in Katowice, Saudi Arabia and the US under President Trump had fought off efforts to “welcome” the findings of the IPCC special report on 1.5C.

Now, the Glasgow text puts the IPCC’s findings front and centre, under the first subheading “science and urgency”. It “recognises” that the impacts of climate change will be “much lower” at 1.5C compared with 2C and “resolves to pursue efforts” to stay under the lower limit.

This puts a slightly stronger emphasis on 1.5C, with the Paris text itself having only said countries would “pursu[e] efforts” to stay below that rise in global temperature.

The pact then reiterates the IPCC special report finding that limiting warming to 1.5C requires “rapid, deep and sustained” emissions cuts, with carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions falling to 45% below 2010 levels by 2030 and to net-zero around mid-century.

(Note paragraph 22 refers to the 1.5C limit in general, whereas an earlier draft of the text had talked of staying below that level “by 2100”, implying potential temperature “overshoot”. Some climate scientists had expressed concern about this draft wording.)

The pact “welcomes” the latest IPCC report and “expresses alarm and utmost concern” at warming having already reached 1.1C, with remaining carbon budgets now “small and being rapidly depleted”.

It “notes with serious concern” that current pledges will see emissions increase by 2030 and starts a work programme on faster cuts “in this critical decade”, with a report due at COP27 next year.

The pact requests a draft decision be drawn up on this matter, meaning the need for increased ambition before 2030 will be formally on the agenda at the next COP – and potentially at future summits.

It also starts an annual ministerial meeting on “pre-2030 ambition”, with the first at COP27.

The pact then “requests” that countries “revisit and strengthen” their targets by the end of 2022 “as necessary to align with the Paris Agreement temperature goal…taking into account different national circumstances”.

This language mirrors the wording in the Paris decision text, which “request[ed]” countries improve their pledges by 2020. It also gives a nod to those developing countries that wanted to emphasise the need for rich nations – or major emitters – to take the lead.

Despite some initial confusion, the “request” to ratchet ambition in 2022 is also stronger wording than in earlier drafts, which had merely “urge[d]” parties to step up next year.

After all the #COP26 debate about whether “requests” is stronger UN-speak than “urges” (it is), here’s a fuller version of the @UNFCCC style guide on how to choose verbs in legal text

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 14, 2021

eg “encourage” is at the weaker end of the spectrum, which runs from “instructs” to “calls” pic.twitter.com/5L1Z7dfUFM

Throughout COP26, many parties and observers called for this tightening of “ambition”.

Ultimately, this “request” is likely to be ignored by some countries in 2022, in the same way that around 40 countries failed to offer new or updated NDCs before COP26.

Nevertheless, the wording sets a clear expectation that all countries will raise their game next year, with intense diplomatic pressure likely to fall on those that refuse to play ball.

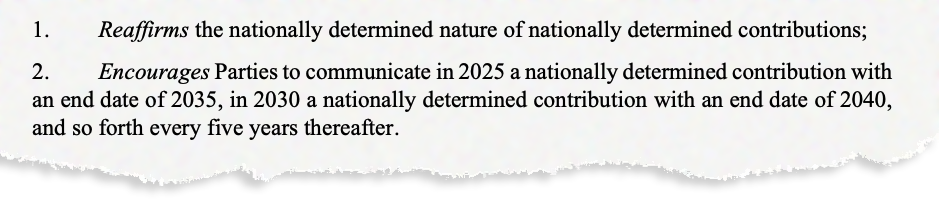

Again, this goes beyond what was agreed in Paris, where countries were only expected to update their pledges every five years – with an option to do so at any time.

The rationale for this is clear. The next round of NDCs are due to cover the period from 2031 onwards, yet a yawning gap remains between current pledges to 2030 and the 1.5C limit.

The pact’s new request to revisit and strengthen 2030 targets next year therefore offers a narrow window through which the 1.5C limit could be kept within reach.

Notably, this language around a 2022 ratchet was agreed, despite some countries having argued against what they saw as a “renegotiation” of the Paris text.

In addition, the Glasgow pact “urges” those that have yet to update their NDCs to do so “as soon as possible” and requests the UN climate body to publish annual updates to its synthesis report, on the combined climate impact of countries’ NDCs.

Similarly, it “urges” those that have not yet submitted long-term strategies to the UN to do so before COP27 “towards just transitions to net-zero emissions by or around mid-century”.

(An earlier draft had called for more specific “plans and policies” towards reaching net-zero, in addition to asking for the strategy itself. This language was subsequently deleted.)

Although much of the language in the pact remains loose rather than binding, it does contain a number of “decisions” and “requests”, in addition to the wording on cutting emissions.

These largely reflect the underlying decisions adopted elsewhere in the COP on matters such as adaptation, finance and loss and damage. Highlights include:

- A two-year Glasgow Sharm el-Sheikh work programme to define a new global goal on adaptation (see: Adaptation).

- A pledge from developed countries to “at least double” adaptation finance between 2019 and 2025.

- Acknowledgement of the loss and damage already being caused by warming and welcome for the operationalisation of the “Santiago Network”. (See: Loss and Damage).

- A two-year Glasgow Dialogue “to discuss the arrangements for the funding of activities to avert, minimize and address loss and damage”.

- A note of “deep regret” that the $100bn climate finance goal has not yet been met, with developed countries “urge[d]” to “fully deliver…urgently and through 2025”. (See: Finance.)

- A pledge to “significantly increase” financial support and a new body to agree the post-2025 finance goal by 2024.

- Repeated references to human rights, the rights of Indigenous peoples’ and gender equality, as well as the need for social and environmental safeguards.

- Recognition of the need to protect, conserve and restore “nature and ecosystems…including through forests and other terrestrial and marine ecosystems”. (This replaced earlier language on “nature-based solutions” to climate change.)

- An invitation for Parties to “consider further actions to reduce by 2030” other greenhouse gases, including methane.

One other paragraph of the pact garnered disproportionate media attention after its wording, according to Politico, “almost sunk the Glasgow climate deal”.

This was paragraph 36 of the CMA text, which in the first draft from the COP26 presidency “call[ed] upon parties to accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels”.

By the time the pact was sealed three days later on Saturday evening, this had been amended to “accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”, with additional text on support for the poorest and the need for a just transition.

The evolution of this text – and the associated language on phasing out (“inefficient”) fossil fuel subsidies – is shown in the table, below.

| 10 November 2021 – 05:51 | Calls upon Parties to accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels. |

| 12 November 2021 – 07:13 | Calls upon Parties to accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies and the adoption of policies for the transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up clean power generation and accelerating the phaseout of unabated coal power and of inefficient subsidies for fossil fuels. |

| 13 November 2021 – 08:00 | Calls upon Parties to accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures, including accelerating efforts towards the phase-out of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, recognizing the need for support towards a just transition. |

| 13 November 2021 – 18:00 | Calls upon Parties to accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures, including accelerating efforts towards the phase-out of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, recognizing the need for support towards a just transition. |

| FINAL AGREED TEXT | Calls upon Parties to accelerate the development, deployment and dissemination of technologies, and the adoption of policies, to transition towards low-emission energy systems, including by rapidly scaling up the deployment of clean power generation and energy efficiency measures, including accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, while providing targeted support to the poorest and most vulnerable in line with national circumstances and recognizing the need for support towards a just transition. |

The language of coal phasedown and inefficient fossil fuel subsidy phase-out can be traced through various recent documents, including the G20 deal in October, the US-China joint statement at COP26 and the words of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

The final shift in language at COP26, from “phase-out of unabated coal” to “phasedown”, was publicly proposed from the plenary floor by Indian environment minister Bhupender Yadav, in the tense final moments of the closing meeting.

After Yadav’s intervention, many countries took to the floor to express their “profound disappointment” at the shift in language, calling it a “bitter pill” and objecting to the way it had been agreed in closed-door negotiations between the US, EU, China, India and UK.

Beyond the rhetoric, the shift in language was largely symbolic, given that even the original text had not set any timelines, making the wording open-ended and non-specific.

Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International, said:

“They changed a word, but they can’t change the signal – that the era of coal is ending.”

Energy experts were also quick to call it a “big deal” for India to accept the phasedown language, as a country with many millions of people still living in poverty and rapidly growing demand for energy. Others noted that India’s target for 500 gigawatts (GW) of renewable energy by 2030 might well imply a phasing down of coal use in any case, if it can be met.

It is the first time that India has explicitly addressed the question of a coal exit, according to Chris Littlecott, associate director of thinktank E3G. He noted that major coal exporters, including Australia, Indonesia and Colombia, had accepted the language of coal phaseout.

Meanwhile, some commentators pointed to the absence of oil and gas in the text, or argued that the real issue was a refusal by the US to discuss a phaseout of all fossil fuels.

Earlier in the week, Yadav had proposed language suggesting that all fossil fuels should be phased down – not just coal – particularly in developed countries, and that developing countries should be able to use a “fair share” of the global carbon budget.

(The IPCC special report on 1.5C and the International Energy Agency’s net-zero emissions pathway both suggest that much more rapid cuts in coal use are needed to stay below 1.5C, relative to what is required of oil and gas – but use of all three will need to be cut.)

In any case, the explicit reference to reducing coal use marked a significant first for the UN climate process, after nearly 30 years of summits.

Reflecting on the draft coal language during the second weeks of the talks, WWF Japan’s Naoyuki Yamagishi had told Carbon Brief: “If this paragraph survives, it makes history.”

Paul Watkinson told Carbon Brief:

“The changes on fossil subsidies and coal were disappointing, but it is still the first time the COP or CMA addresses them directly and the message is still there. The rest of the content could have been better and stronger in many ways, but it is a basis for strengthening action and implementation on mitigation, adaptation, means of implementation, and loss and damage.”

Indeed, the Glasgow Climate Pact reflects some, but by no means all of the requests made by various groups ahead of and during the summit.

It picks up on many of the “proposed elements” set out by the UK presidency in the first week, which, in turn, followed consultations at COP26 and in the months leading up to it.

NEW

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 7, 2021

“Non paper” on “possible elements” of crucial #COP26 “cover decision” aka 1/CP.26 1/CMA.3 1/CMP.16

It’s a grab-bag of everything that could be included, not yet drafted in legalese, from “keeping 1.5C alive” to human rights to loss & damage financehttps://t.co/aaDWMzPiHO pic.twitter.com/1BKZzhkG2V

Most controversially, however, it does not establish a “Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility”, a financial mechanism to respond to current climate damages, which was proposed by the G77/China group of developing countries with wide support (see: Loss and damage).

At the start of the COP, the Climate Vulnerable Forum (CVF) – a group of 55 nations particularly exposed to climate impacts – had issued a call for a “Climate Emergency Pact”.

This included an annual call for stronger climate pledges from all countries, “but especially the major emitting countries”, as well as asking for at least $500bn in climate finance during 2020-2024, split 50-50 between mitigation and adaptation.

In the first week, another pitch for the cover text came in from the High Ambition Coalition (HAC) of small island states, the least developed countries, the EU and others.

Significant #COP26 intervention from High Ambition Coalition (🇺🇸🇩🇪🇬🇦🇫🇯etc) calls for

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 2, 2021

▶️1.5C aligned NDCs b4 COP27

▶️net-zero goals b4 2023 stocktake

▶️no new unabated coal + coal phaseout

▶️loss & damage “resources”

▶️$100bn

▶️adaptation $ “balance”

1/https://t.co/bEZM7C2XdW pic.twitter.com/ixCK0V26Wa

The HAC had helped drive through the Paris Agreement in 2015, particularly its inclusion of the 1.5C ambition, and its heft was increased as the US rejoined near the start of COP26.

However, it had a lower profile in Glasgow, with the EU in particular coming in for criticism for failing to take a more prominent role in the coalition – and at the summit more generally.

Finally, a letter from the “friends of the COP”, an international expert group set up by the UK presidency, was published in the last days of the summit with a series of suggestions for improving the “balance” of the Glasgow cover text.

Finance

Money was, perhaps, the issue that defined the COP26 negotiations more than any other, permeating virtually every aspect of the talks.

This was not a new development. Since their inception in the mid-1990s, these negotiations have seen poor and vulnerable nations trying to convince wealthier, high-emitting states to provide them with climate finance.

However, this year’s event came shortly after rich nations acknowledged that they had failed to meet a $100bn annual climate finance target for 2020, which was set over a decade ago.

This failure framed COP26 from the outset. Many of the global-south leaders who spoke during the first two days drew attention to it and delegates expressed concerns about a breakdown of trust between parties.

Dr Emmanuel Tachie-Obeng, representing the Climate Vulnerable Forum, expressed many parties’ frustrations to Carbon Brief:

“I believe that the money is there – they don’t want to release it. Because looking at Covid…billions of dollars have been used over the years to take care of Covid. Do you think Covid is more important than climate change?”

The disconnect between pledges and reality was exemplified by COP26 finance adviser Mark Carney’s questionable suggestion that $130tn of private capital was committed to achieving net-zero emissions.

Mohamed Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, noted in a press briefing that with countries failing to muster even $100bn per year, “how much can we trust that they are serious?”.

Demonstrating credibility on this issue was seen as an important issue. The COP26 decision text (below) “notes with deep regret” that the $100bn goal has not “yet” been met – misleading wording given that it had a set target date of 2020 and is not currently expected to be met even this year.

A “delivery plan” released by the COP presidency ahead of the event set out how richer nations would deliver the money by 2023, although new funding from Japan may push them over the line a year earlier.

So @JohnKerry just said that while rich countries missed their 2020 $100bn climate finance target, they did get to “between 95-98” according to @OECD.

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) November 2, 2021

Not clear what he means by this – OECD analysis suggests we’ll reach $92-97bn…but not until 2022https://t.co/F4UH3qQPtQ pic.twitter.com/Mjd4E8ARPY

The final text “urges” them to meet the target “urgently and through to 2025”. However, it lacks any wording on making up the shortfall in the years 2020-2022 when the target is expected to be missed.

Another key issue for developing countries was the quality of climate finance.

Many of the poorest nations and small island states struggle to access these funds. Belizean negotiator Janine Felson, who is also the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) lead on finance, told Carbon Brief that this was a key issue for them:

“If climate finance is not predictable, accessible, grants-based and most importantly significantly scaled up, it seriously undermines the entire credibility of the Paris Agreement.”

As it stands, financial streams such as high-interest loans are often included in climate finance reports despite criticism. NGOs estimate that the amounts being mobilised are a fraction of the totals quoted by rich nations.

Throughout the negotiations wealthy countries resisted calls for a working definition of “climate finance”, something long advanced by developing countries that could clarify exactly what counts towards these totals.

Who would have thought that at @COP26 after developed countries confessed that they failed to meet the obligation of mobilizing $100 bn by 2020 that they would object to having a multilaterally agreed definition of climate finance. I guess it may be a transparency issue.

— Zaheer Fakir (@zaheer_fakir) November 9, 2021

Several streams of the negotiations centred around finance, with the key battlegrounds centring around loss and damage and adaptation, as well as how these historically underfunded issues would be supported. (See: Loss and damage and Adaptation sections.)

There were also two technical areas that were addressed: the “new collective quantified” post-2025 goal for finance, which will ultimately supersede the $100bn target, and discussions around “long-term climate finance”.

Unlike the $100bn, the post-2025 goal is being negotiated as part of the UNFCCC process. This time, developing countries wanted to see scientific analysis of their needs being used to inform it.

A recent assessment by the UNFCCC’s Standing Committee on Finance concluded that these nations would require nearly $6tn up to 2030, including domestic funds, to support just half of the actions in their NDCs.

Another priority for these parties was for a stream of funding within the new goal to support “loss and damage”, although observers reported that the US, in particular, opposed this idea. (See: Loss and damage.)

Negotiations around the post-2025 target were never expected to be concluded at this COP and are set to continue for another three years. Nevertheless, some nations did make suggestions that give a sense of how much money they think will be needed.

A quote of $1.3tn per year with a “significant percentage on a grant basis”, which was put forward by the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) and the African Group, appeared in an earlier text, but had been removed by the next draft.

From draft text on long-term finance, three options for a new global finance goal (i.e. annual climate finance for the years 2025-2035) – (1) general commitment to increase finance, (2) process towards setting a quantified goal, (3) a process towards a specified quantity. #COP26 pic.twitter.com/PC92vMlFDP

— Tarun Gopalakrishnan (@tarungk91) November 11, 2021

Wealthier nations had their own priorities in negotiations. “The issue that the developed countries want discussion about is who contributes to the new goal – broadening the donor base,” Jan Kowalzig, a climate finance expert at Oxfam, told Carbon Brief.

The list of countries obliged to provide finance under the UNFCCC is based on those that were members of the OECD in 1992. Therefore, it does not include wealthy countries, such as South Korea or the oil-rich Gulf states.

However, expanding the list of contributors has not proven popular, especially given the failure of contributor nations to mobilise finance as promised. Diego Pacheco, lead negotiator for Bolivia and spokesperson for the LMDCs, told Carbon Brief:

“This idea of expanding on…the question of who is going to provide finance to the new quantified collective goal is not serious, is not responsible, [for] countries trying to take the lead on climate action.”

Bolivian negotiator at #COP26 for the LMDCs – group that includes China and India – emphasises that countries are not all equally responsible for climate change. “History matters.”

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) November 11, 2021

Also says “developed countries have a history of broken promises.” pic.twitter.com/sOE9kOeNix

In the end, specifics such as language around loss and damage or expanding the donor base did not make it into the final text for this agenda item. Instead, it focused mainly on an “ad-hoc working programme” set to take place in the coming years with expert input and discussions with ministers.

The second finance-specific agenda item was on “long-term climate finance”, which sounds similar to the post-2025 target, but, despite its name, actually refers to the missed $100bn target, which finished in 2020.

Developing countries wanted to keep this discussion open until the new finance target comes into play and use it as a venue in which to discuss improving the quality and share of adaptation finance. Wealthier countries argued that the agenda item could simply be closed.

“We need that accountability,” Meena Raman, a legal adviser with the Third World Network, told Carbon Brief. “We need long-term finance on the agenda to talk about pre-2020 commitments, which need to be met.”

The final decision on this agenda item agreed to keep discussing long-term finance until 2027, reflecting a lag in reporting that means 2025 finance figures will not be available until two years later.

Lorena González, climate finance lead at the World Resources Institute (WRI), told a press briefing after the event closed that all parties were somewhat “unsatisfied” with the results of finance negotiations, reflecting compromise on all sides.

“COP26 has put into place the scaffolding for the post-2020 finance landscape,” she said.

Ultimately, in the coming years, leaders will need to work out ways of turning the “billions to trillions” in total climate finance, something acknowledged by the UK presidency from the outset.

Outside of the formal negotiations, Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley called for $500bn of special drawing rights – reserve currency normally issued during crises – as an alternative instrument to mobilise money on the scale required.

“We’re getting pledge fatigue,” economist and Barbados special envoy Avinash Persaud told Carbon Brief.

Article 6

Note 24/11/2021: This section has been amended to clarify the text on REDD+.

After four years of negotiations, countries meeting at COP26 finally reached a deal on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which covers international cooperation including carbon markets.

The lengthy process had stemmed from fears that the rules, if poorly designed, could “make or break” the entire Paris deal. The high stakes were exacerbated by intensely political disagreements, laced with technical jargon, over a number of fundamental principles.

(For background and explanations of all of the jargon, politics and technical matters relating to this, see Carbon Brief’s Q&A on Article 6 and coverage of discussions at COP25.)

In the end, all parties were forced to make significant compromises on their starting positions, with multiple negotiating alliances having to breach their “red lines”.

Specifically, parties agreed to the “carryover” of carbon credits generated under the Kyoto Protocol since 2013, bringing up to 320m tonnes of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e) into the Paris mechanism.

(More than 4bn credits might have been carried over if the transition had been unrestricted.)

In addition, COP26 decided that adaptation finance from a “share of proceeds” of trade in emissions cuts would only be mandatory under part of Article 6, remaining voluntary elsewhere.

On the other hand, the rules agreed in Glasgow closed off the “double counting” of emissions cuts by two different countries or groups, sometimes referred to as “double claiming”.

The rules effectively excluded the use of credits generated historically, between 2015 and 2021, from reduced deforestation and forest degradation, under the UN scheme known as REDD+.

They also signaled that disputes around carbon-offsetting projects will be subject to an independent grievance process, meeting a key ask from Indigenous and environmental groups.

Nat Keohane, president of the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, told Carbon Brief the deal was stronger than he had expected on avoiding double counting, but “disappointing” in relation to the carryover of Kyoto credits. He added:

“Buyers have a role to play in ensuring integrity by refusing to accept them.”

Article 6 itself contains three separate mechanisms for “voluntary cooperation” towards climate goals, with the overarching aim of raising ambition. Two of the mechanisms are based on markets and a third is based on “non-market approaches”. The Paris Agreement’s text outlined requirements for those taking part, but left the details – the Article 6 “rulebook” – undecided.

Article 6.2 governs bilateral cooperation via “internationally traded mitigation outcomes” (so-called ITMOs), which could include emissions cuts measured in tonnes of CO2 or kilowatt hours of renewable electricity.

It could see countries link their emissions trading schemes, for example, or buying offsets towards their national climate goals. (No numerical limits were placed on this use of offsets.)

Article 6.4 will lead to the creation of a new international carbon market for the trade of emissions cuts, created by the public or private sector anywhere in the world.

Article 6.8 offers a formal framework for climate cooperation between countries, where no trade is involved, such as development aid.

COP26 reached decisions on each of these sections:

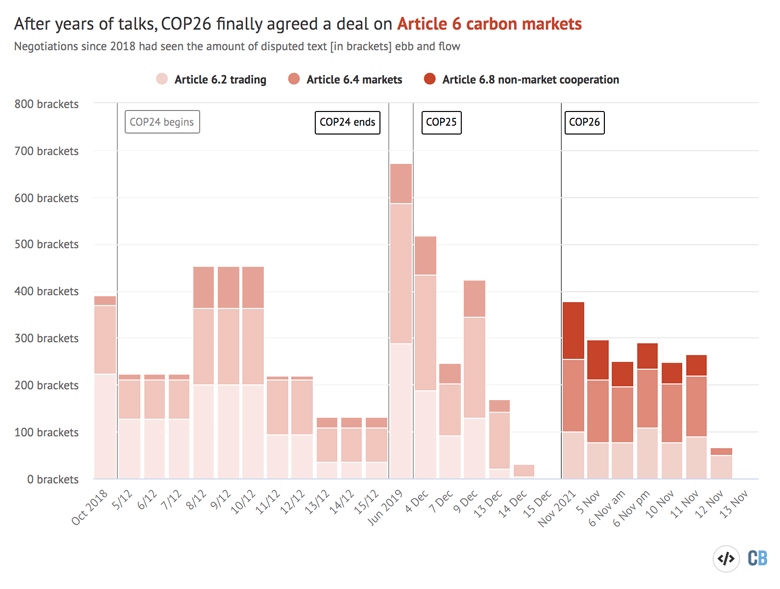

Agreeing the Article 6 rules has been a rollercoaster ride. The figure below shows how draft negotiating texts have evolved over time, in each of the three parts of Article 6, with the height of the columns indicating the number of unresolved text in square brackets.

Although negotiators came close to a deal at COP25 in Madrid – as the chart above shows – they were ultimately unable to get over the line, leaving discussions to resume on the road to Glasgow.

Multiple negotiators and observers told Carbon Brief that the manner of discussions at COP26 was in marked contrast to previous talks, with many commenting on a spirit of cooperation.

Brad Schallert, director of carbon markets and aviation for WWF, told Carbon Brief during the first week of the summit that the difference was “palpable”, even though progress was initially slow.

The “breakthrough” moment came towards the end of the second week, when a “bridging proposal” – understood to have come from Japan – offered a way around the long-disputed question of how and when to apply “corresponding adjustments” to national emissions inventories, so as to avoid “double counting”.

The proposal makes a subtle shift to the moment when “corresponding adjustments” have to be applied, from the point of use to the point of authorisation by a host country.

Whether as a result of this idea or thanks to a greater willingness to compromise, the proposal soon gained support from the US and Brazil, before ultimately being adopted by all countries.

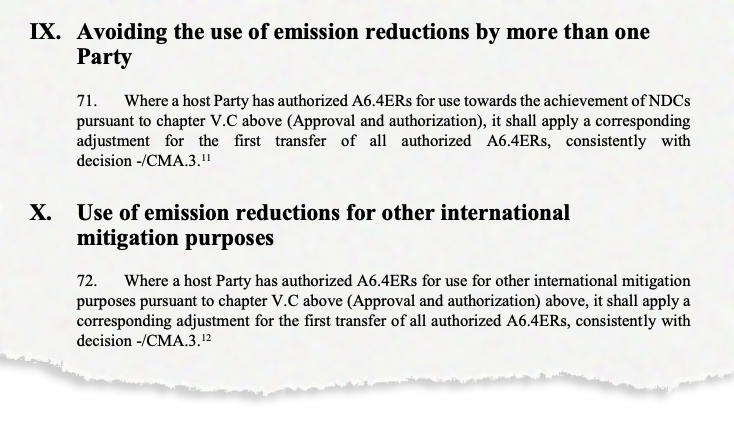

Crucially, the rules require “corresponding adjustments” to be made for all authorised carbon credits under Article 6.4, whether they are used towards meeting countries’ NDCs or for “other international mitigation purposes”, such as the UN aviation offset scheme CORSIA.

Similarly, the decision adopted in Glasgow requires that corresponding adjustments are made under Article 6.2, relating to bilateral trade between countries.

This is more complicated to put into effect, because many countries’ NDCs have a single target year, such as 2030, whereas carbon credits might be bought across multiple years.

Moreover, some countries have not set targets in terms of emissions, but in terms of goals, such as an increase in their renewable energy capacity.

The Article 6.2 rules offer various ways to account for these issues, one of which – known as “averaging” – creates a risk of “double counting” and increased emissions, according to Lambert Schneider, research coordinator for international climate policy at Oeko-Institut.

One remaining grey area is the term “other international mitigation purposes”. This could include the voluntary carbon markets, where businesses buy offsets towards their corporate goals.

If a company buys an offset from a country overseas, which is authorised for “other international mitigation purposes”, then it will be accounted for via corresponding adjustments.

This would work as follows. The buyer would “own” the emissions reduction and could claim it against its own emissions total – for example, towards a corporate net-zero target – while the host country would have to apply a corresponding adjustment to its own inventory, to reflect the sale.

On the other hand, the text implicitly allows non-authorised credits to be issued, which would not be subject to a corresponding adjustment – creating a risk of double counting.

An earlier draft of the text had included the option to explicitly manage this issue, via the creation of second-tier “Paris Agreement Support Units”.

in 6.4, the talk about text creating a “2-tier” system relates to the section pictured, where credits subject to corresponding adjustment to avoid double counting (PAAUs) would be treated differently to those that aren’t (PASUs)

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 12, 2021

HT @CarbonReporter pic.twitter.com/rDF8esYvOQ

A company buying one of these units would not have been able to claim the emissions reductions for itself, with the transaction instead being likened to “results based finance” – effectively, it would have been contributing to the meeting of the host country’s climate goals, but not its own.

Various reactions to the Article 6 deal emphasised the need for market participants, including in voluntary markets, to only claim emissions reductions backed by a corresponding adjustment.

In a statement, Carbon Market Watch policy officer Gilles Dufrasne said:

“Double-counting of emission reductions defies logic and would be a futile attempt to cheat the atmosphere. The agreement reached in Glasgow sends a signal that this cannot be tolerated and voluntary carbon market actors have been put on notice: companies cannot use emission reductions which happen under existing climate targets as carbon offsets anymore.”

Similarly, Schneider wrote:

“Ultimately, governments or courts may start regulating what claims companies can truthfully make in association to carbon credits that are not backed by corresponding adjustments.”

Other decisions included in the rules include allowing projects registered under the Kyoto Protocol to become part of the Article 6.4 mechanism, subject to meeting its new methodologies by 2025.

According to Schneider, in the decade to 2030 up to 2.8bn carbon credits could be generated by these projects, many of which are wind and hydro schemes that will continue to operate whether or not they are able to sell offsets under Article 6.

This means the emissions “reductions” they generate would not be truly additional to what would have happened otherwise, yet they could be used to avoid making genuine cuts elsewhere.

In practice, Schneider notes, there are reasons to believe this may be a smaller problem than feared. Either way, these credits – along with the roughly 300m pre-2020 Kyoto offsets – will be clearly labelled, setting up potential reputational risks for buyers choosing to use them.

In a statement, Keohane said:

“To ensure environmental integrity, countries should refuse to use pre-2020 credits from the [Kyoto Protocol’s] Clean Development Mechanism to meet their NDCs – instead focusing on new emissions reductions. Civil society will be watching.”

The impact of pre-2020 credits on the atmosphere has already been accounted for in the cumulative total of CO2 that has been released to date.

Felipe De León Denegri, Article 6 negotiator for Costa Rica, told Carbon Brief that allowing them to be used again towards Paris pledges therefore amounts to “double counting by time travel”.

(Kyoto offsets can only be used towards countries’ first NDCs in the period to 2030.)

Regarding REDD+ emissions savings from reduced deforestation, Papua New Guinea led ultimately unsuccessful efforts at the COP to automatically include old credits generated during 2015-2021 in the Article 6.2 mechanism.

With other members of the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, it was pushing text contained in early drafts – but not the final decision – that would also have fast-tracked the entry of new REDD+ credits generated under the scheme. REDD+ credits generated from 2021 onwards could still be used, subject to meeting the wider Article 6 rules.

Elsewhere, the rules agreed that parties will be “strongly encouraged” to contribute money for adaptation and to cancel some offsets to deliver “overall mitigation” when trading under Article 6.2.

For Article 6.4, a mandatory 5% of traded offsets will be cancelled, with the money going towards the Adaptation Fund, while another 2% will be cancelled to deliver “overall mitigation”.

Developing countries had been pushing for much higher rates of cancellation and for these rates to be mandatory and equalised between the two schemes under Articles 6.2 and 6.4, but, ultimately, had to give way in the face of implacable opposition from the likes of the US and EU.

In combination with the transition of Kyoto-era credits and activities, the low levels of mandatory cancellation for adaptation and overall mitigation amount to “something of a worst-case scenario for the climate”, according to the NewClimate Institute, a thinktank.

1/4 #Article6 negotiations at @COP26 look like they’re targeting something of a worst-case scenario for the climate (yellow circle, bottom right) @EspenBarthEide @MSEsingapore pic.twitter.com/IEcku38Ixt

— NewClimate Institute (@newclimateinst) November 13, 2021

The Article 6 rulebook also decided the following matters:

- An Article 6.4 “supervisory body” will start work in 2022 at two meetings, where it will begin to draw up methodologies and administrative requirements for the market.

- Further technical work will develop guidance on how to apply corresponding adjustments, in particular relating to the question of double counting and single-year NDCs.

- Technical work will also look at whether to allow credits from “emissions avoidance”.

- In 2028, a review will consider whether to apply additional safeguards or limits on the use of credits under Article 6.2.

- A Glasgow Committee on Non-Market Approaches is established to take forward the development of climate cooperation under Article 6.8, with the committee due to meet twice a year until at least 2027.

Loss and damage

COP26 saw loss and damage emerge as a key dispute, dragging out the negotiations as developing nations and island states refused to back down in their urgent calls for money to help vulnerable communities.

In the end, strong opposition from rich countries saw the issue largely delayed until next year, despite some progress in discussions around a new technical support body.

The term “loss and damage” refers to unavoidable impacts of climate change that cannot be adapted to, from flooded villages to drought-struck farms. It is sometimes framed as “climate reparations”.

Vulnerable nations want money and support for people threatened by such impacts. However, wealthy countries have consistently resisted this idea, fearing that they will be forced to pay compensation due to their historical responsibility for climate change.

As COP26 proceeded, much was made of the prominence that loss and damage had in both the hallways and negotiation rooms. Many delegates described this focus as unavoidable given the escalating deaths and costs linked to climate change around the world.

On the first day of the summit, the island nations of Tuvalu and Antigua and Barbuda announced the launch of a commission that could pave the way for them claiming damages from major emitters through the courts.

“Should no formal mechanism for #lossanddamage compensation be established, member countries of the UN may be prepared to seek justice in the appropriate justice bodies” by @gastonbrowne , PM of #AntiguaandBarbuda at #COP26Glasgow – High-Level Segment pic.twitter.com/xcdoi4vg8s

— Loss and Damage Collaboration (@LossandDamage) November 1, 2021

But the main loss and damage focus was in the negotiations themselves. The UK presidency appeared confident about some kind of positive outcome after years of slow progress on the topic.

Since the Paris Agreement in 2015 loss and damage has, in theory, been the “third pillar” of international climate policy, but, in reality, it has often been overlooked in climate negotiations.

Unlike the first two pillars – mitigation and adaptation – there had, prior to this COP, never been any specific funding set aside for loss and damage.

Instead, UN negotiators agreed on a Warsaw International Mechanism (WIM) in 2013, which has functions including research, “strengthening dialogue” and “enhancing” action and support.

None of this involves directly providing money to vulnerable communities.

Going into COP26, the key agenda item regarding loss and damage was the Santiago network, a new body created at COP25 in 2019. This was seen as a step forward because it has the potential to address the long-overlooked “action and support” element of the WIM.

Harjeet Singh, a loss-and-damage expert with Climate Action Network (CAN) International, told Carbon Brief that this was a much-needed step so that parties “are not just going to WIM meetings and just talking about it, generating papers, while people are dying”.

At present, the Santiago network exists as a website set up by the UNFCCC, with links to organisations such as development banks that could support loss and damage.

A priority for many developing country groups at COP26 was to “operationalise” the network, providing it with money and staff, and assigning it with responsibilities so that nations could use it to request assistance – for example, by filling in a form on the website.

Laura Schäfer from the NGO Germanwatch told Carbon Brief as negotiations got underway that nations had already had plenty of time to “exchange views on form and function”, noting that this element “should really be decided here” rather than being pushed to COP27.

Developing countries made it clear they wanted a network that could also support them in accessing finance for loss and damage. By contrast, climate NGOs said wealthy countries were happy for the network to remain as nothing more than a website.

Jacob Werksman, a lead negotiator from the European Commission, laid out a more developed idea of what they were looking for at a press conference early in the COP.

He said the network should be a way of bringing together the various pre-existing international agencies set up to deal with natural disasters and ensure that they were up to the challenge of climate change. He added:

“[It should have] the mandate and capacity to deal with things like early warning systems [and] insurance schemes that can help those that wouldn’t otherwise be covered by private insurance schemes. These agencies have been set up over decades to deal with extreme weather events and they are the right way to deal with it.”

As the conference progressed it became clear that the Santiago network would not, in fact, be operationalised in Glasgow, even though technical work deciding on its functions concluded early in the second week.

The WIM text that emerged from the summit indicated that the network would identify and connect interested countries with technical assistance, to help them assess current and future loss and damage. The final decision text stated that “further operationalisation” would follow at subsequent meetings.

The COP26 decision text also “urges” developed countries to provide funds for the “operation of the Santiago network and for the provision of technical assistance”.

This funding is not expected to be particularly large and will initially only support a small staff. The German government has already come forward with an offer of €10m ($11.5m) to support the network.

As the COP drew to a close, developing country parties welcomed the progress made on defining the functions for the Santiago network.

However, throughout the negotiations, the more significant battleground was over the perennial issue of how to get money flowing for loss and damage.

In the first week, Simon Stiell, the environment minister for Grenada, told Carbon Brief that while the Santiago network could “add value”, nations like his required far more from the loss and damage talks:

“That in itself is not going to be enough for vulnerable states. There has to be some mechanism that speaks to loss and damage finance, so it goes beyond just stating the importance of loss and damage.”

Vulnerable countries wanted this to be the COP where loss and damage finance was finally offered up and there were calls for a standing agenda item besides the WIM that could address this.

The issue received an unexpected boost in the first week from Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon. Her pledge of £1m, later doubled to £2m, to “address” loss and damage was welcomed because, while small, it was also the first money ever committed specifically towards this cause.

“The true leader at #COP26 is @NicolaSturgeon”

— Fridays For Future Bangladesh (@FFFinBD) November 12, 2021

Scotland hailed by @SaleemulHuq of @TheCVF for being the ONLY country to pledge separate funding for climate-induced loss and damage in the global south.

“US is giving us zero dollars. Europe is giving us zero Euros.” pic.twitter.com/VZfLcJEbFr

However, even after Sturgeon’s announcement, Schäfer told Carbon Brief that there was “definitely no appetite” for loss-and-damage finance from wealthy countries.

Developing nations and climate campaigners wanted language in the COP26 cover text that made it clear rich countries would commit new money to loss and damage.

There was also a push from developing countries for such funding to form a third stream besides mitigation and adaptation funds in the post-2025 finance target. (See: Finance.)

A draft text that emerged on Wednesday was notable in that it “urged” developed countries, NGOs and private donors to fund loss and damage. However, it lacked any specific financial commitments.

As the day progressed, vulnerable countries began expressing their dissatisfaction with the text. The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) came forward with a significant proposal for a new facility to support loss and damage with “dedicated financing”.

Last night @SaleemulHuq at @TheCVF press conference called for the formation of a “Glasgow financial facility for loss and damage” at #COP26

— Josh Gabbatiss (@Josh_Gabbatiss) November 11, 2021

Small island states AOSIS have backed the idea and I understand the G77 coalition of developing countries is uniting around it as well

By the next day, support for this “Glasgow financial facility for loss and damage” was gathering momentum and had the weight of the G77 + China coalition of developing countries behind it.

Given the urgency of loss and damage, there was pressure to simply announce the facility and hash out the details later.

Before heading in for another round of talks, Pascal Girot, a loss-and-damage negotiator for Costa Rica, told Carbon Brief that countries urgently need short-term finance, but acknowledged that “you can’t just pull these resources out of a hat”:

“We need to hopefully create the mechanism here and then work it out during the next subsidiary body meetings and the next COP.”

On Friday morning, a new text emerged that included a mention of a “technical assistance facility to provide financial support for technical assistance”.

Yamide Dagnet, director of climate negotiations at the World Resources Institute (WRI), told reporters that the loss-and-damage text was the “start of a breakthrough” on this issue.

However, developing countries were quick to register their disappointment, stating that this was not the facility they had in mind.

Rather than money being given directly to vulnerable nations to assist in disaster recovery, observers said “technical assistance” suggested funds to pay consultants, likely in the global north, for help with capacity building in poorer nations.

#Kenya welcome the further operationalisation of the #SantiagoNetwork, but disappointed over the lack of reference to the #GlasgowLossandDamageFacility.

— Angelica Johansson (@ThinkAnge) November 12, 2021

‘We do not need more consultants flying across the globe teaching us about #LossAndDamage‘, i.e. tech assistance not enough.

Dr Siobhan McDonnell, a loss-and-damage negotiator for Fiji, told Carbon Brief that while such support was “desirable”, they should not be asked to trade it off for proper loss-and-damage finance. There were concerns from civil society that this alternative facility would be used to “silence” further finance discussions.

As COP26 went into overtime on Friday evening, it became clear that this matter was one of the key issues holding up negotiations, with the US and the EU both accused of blocking attempts to insert language about finance. Developing countries, meanwhile, were making it clear that the requirement for a new finance facility would be a red line for them.

In an apparent move to encourage the “Glasgow facility” into existence, three leading philanthropic groups that evening pledged £3m to the cause and encouraged developed country parties to join them.

But the new text that appeared on Saturday morning contained no reference to any kind of facility.

Instead, a new paragraph had been inserted (below) “deciding” that a “dialogue” would be established to “discuss the arrangements” for funding. Civil society groups said this was “even worse” than the previous day’s text and Mohamed Adow of Power Shift Africa told Carbon Brief it amounted to a “never-ending talk shop”.

The developed countries; the EU, US and UK, are resisting. It’s important that developing countries don’t fall into the trap of an endless dialogue and are better off deleting all mention of unnecessary dialogues from the text.

— Mohamed Adow (@mohadow) November 13, 2021

Nevertheless, by the time of the informal plenary session that afternoon, nations were striking a more conciliatory tone.

Guinea, speaking for the G77 + China, said that, while they were disappointed with such a dialogue, they were willing to compromise. Others stated that they would sacrifice loss and damage finance in order to save the deal.

Ultimately, the only loss-and-damage financial demand that made it into the final text was for richer nations to support the Santiago network.

However, with 12 mentions of loss and damage making it into the final “Glasgow pact”, there was hope that this issue could be reignited at COP27.

“Loss and damage is now up the political agenda in a way it was never before and the only way out is for it to be eventually delivered,” said Adow.

Adaptation

Going into the conference, the only formal agenda item focused on adaptation was to discuss the reports of a technical group called the Adaptation Committee. But that quickly changed, with the issue featuring in a range of inter-related negotiations and campaign demands.

All nations will need to adapt to global warming, whether that means building flood defences to cope with rising sea levels or installing more air conditioning as summers become unbearable.

However, this is a particular concern for global-south nations that disproportionately face the most extreme impacts of climate change, but often lack the resources to prepare for them. Adaptation funding was, therefore, widely seen as a key priority going into this COP.

The Paris Agreement calls for a balance between different types of climate finance, but currently it is heavily skewed towards mitigation activities, such as renewable energy projects, which are often seen as better investments.

After some fractious negotiations, developing countries scored a victory when the final text of the “Glasgow climate pact” settled on a call for developed nations to “at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation” from 2019 levels by 2025.

Earlier drafts used vaguer language, at first only “calling upon” developed countries to “at least double” their adaptation finance, but providing no baseline or target date for this shift.

Over the course of negotiations this text was tightened so that countries were “urged” to act.

The language also shifted to calling for the doubling to happen by 2025 – at first “from the current level” and the, ultimately, clarifying that this meant 2019, the most recent year for which climate finance figures are available from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

This would mean that, by 2025, developed countries should mobilise $40bn in adaptation funding.

While this would be a significant improvement on current levels, it is a fraction of the amount that is needed. For example, the UN Environment Programme places annual adaptation costs for developing countries today at $70bn, but estimates that this could quadruple by 2030.

Civil society groups tentatively welcomed this progress, while emphasising that there is still a long way to go in providing adequate adaptation financing.

Another key development for adaptation finance came in the form of record-breaking pledges to the Adaptation Fund, including new announcements from the US and EU.

Again, this funding is a fraction of the billions required by developing countries, but the fund has the advantage of being focused exclusively on adaptation projects and also being 100% grant-based rather than providing loans to poorer nations.

New @adaptationfund pledges at #COP26:

— Joe Thwaites (@joethw8s) November 9, 2021

🇪🇺$116.4m

🇩🇪$58.2m

🇺🇸$50m

🇪🇸$34.9m

🇬🇧$20.6m

🇸🇪$15.1m

🇨🇭$10.9m

🇳🇴$8.38m

🇨🇦$8.1m

🇫🇮$8.1m

🇨🇦⚜️$8.1m

🇮🇪$5.8m

🇧🇪🦁$3.49m

🇧🇪💛$2.6m

More than double previous annual fundraising record (COP24) and increases fund size by 40%!https://t.co/JVTV1pap6P

In a reflection of concerns about a shortfall in adaptation funding, African nations, in particular, pushed for a “share of proceeds” in Article 6 negotiations, hoping this could provide an alternative source of adaptation funding. (See: Article 6.)

Another notable development at the conference was the first-ever addition of a “global goal on adaptation” to the agenda, as the conference began on Sunday.

Although this concept is laid out in Article 7 of the Paris Agreement (see below), some parties argue that it is unclear what it is or how progress on adaptation can be quantified.

African nations, which already spend large portions of their GDP on adapting to climate change, have been pushing for a quantitative and qualitative goal, as well as ways to make it operational.

This is viewed as part of an effort to put adaptation on a par with mitigation within the UNFCCC’s agenda, but developed countries have argued that it is not necessary.

Parties such as the US have stated that any work in this area should be confined to the Adaptation Committee. But Eddy Pérez of CAN Canada told Carbon Brief this was another example of adaptation being pushed down the agenda:

“Instead of having a ministerial discussion…bringing it to the Adaptation Committee would signal that it is just another technical issue that we need to give to negotiators and it’s going to get lost.”

In the end, the conference produced a two-year “Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work programme on the global goal on adaptation”, which recognised the need for “additional work” to help countries measure and track adaptation.

Parties will be able to provide submissions with metrics to assess how far they have come. This will be assembled into synthesis reports to measure progress against the global goal.

Mima Holt, a research associate at World Resources Institute, told Carbon Brief that all of this was another win for those pushing an adaptation agenda, noting that the outcome largely mirrors a proposal submitted by Gabon at the start of the COP:

“The African Group has been pushing and submitting proposals for a few years now for how to go about the global goal on adaptation, so this is very good progress.”

On finance, developing countries won one demand but not others. The agreement requires rich countries to ‘at least double’ funds for adaptation (ie coping with present climate change). This is what poor countries need the most; presently it’s only 25% of finance flows. /5

— Michael Jacobs (@michaelujacobs) November 14, 2021

Transparency

Rules on transparency of climate action and support – one of the last unresolved parts of the Paris rulebook – were finally decided at COP26, but not without considerable effort.

On a very basic level, the transparency rules are about ensuring countries report sufficient information to determine whether or not they are meeting their pledges, whether the world is on track to reach its climate targets, and, crucially, whether this information is reliable.

This is widely seen as key to the Paris process, which relies on promises made by each country being kept. Transparency allows for peer pressure, to help this happen.

“Why does transparency matter? The whole climate regime rests on transparency,” Pete Betts, the UK and EU former lead negotiator, told a press briefing in Glasgow. He added:

“There are no penalties in the climate regime, there’s only naming and shaming…Having a functioning transparency regime is absolutely key to the whole system working.”

As it stands, only the countries that were identified as wealthy when the UNFCCC was established in 1992, which include European nations, the US, Japan and Australia, have to report regularly on their greenhouse gases and other relevant topics, such as finance.

This means there are big holes in the availability of data for some major emitters.

Iran has not filed an emissions inventory with the UN since 2010, China since 2014 and India since 2016, according to a recent Washington Post investigation, which also raised question marks over the reliability of some of the reporting.

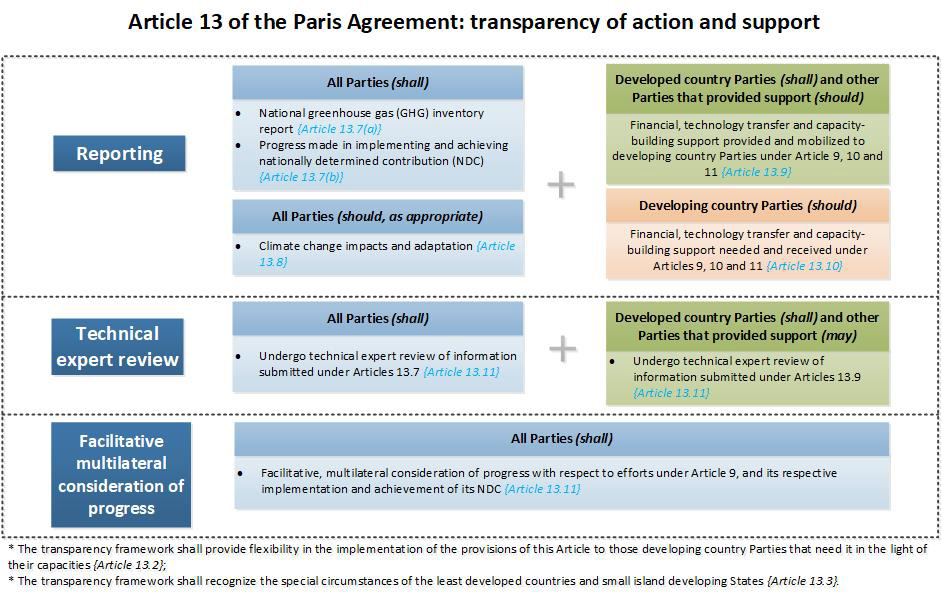

However, Article 13 of the Paris Agreement established the “enhanced transparency framework”, which aims “to build mutual trust and confidence and promote effective implementation” through the provision of information on “action and support”.

Under this new framework, all countries will have to report their emissions, progress towards their climate pledges and their contributions to climate finance, at least every two years.

In addition, parties are expected to report on climate impacts and adaptation. All reporting will be subject to a “technical expert review” and a peer-review process known as a “facilitative multilateral consideration of progress”.

This is a major change from the previous regime, which had different requirements for developed and developing nations.

The text offers relatively open-ended flexibility to “those developing country parties that need it in light of their capacities”. However, this and other details were further defined at COP24, which adopted the “modalities, procedures and guidelines” (MPGs) for transparency.

According to these MPGs, countries must submit their first “biennial transparency report” and “national inventory report” by the end of 2024, with small island developing states and the least developed countries allowed to do so “at their discretion”.

(At COP24, some countries had argued in favour of earlier reporting, so as to inform the first “global stocktake”, due to take place in 2023. This will not now be possible.)

The MPGs also set out “guiding principles”, according to which the use of flexibility will be “self-determined”, but, where it is used, it must be clearly indicated and justified.

This is so that “capacity building needs” can be identified and so that incomplete reporting and transparency can be improved over time.

The key question facing negotiators at COP26 was to define what should be in countries’ emissions inventory reports and progress updates, as well as how they should indicate the use of flexibility – and how they should present a “structured summary” of their results.

The nub of the #COP26 negotiations is *how* do countries report?

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 9, 2021

* common reporting tables for emissions inventory

* common tables for progress reporting

* common tables for support inc $$$

They’re deciding what, specifically, is in the tables pic.twitter.com/vkPqFWYXwr

While, on the face of it, these talks seem incredibly technical and, hinging as they do on the creation of spreadsheets and other methods of reporting data, unlikely to cause much controversy, they provided a major source of conflict at COP26.

At COP25, the transparency rules were thrown forward to Glasgow, but with countries approaching the reporting deadline there is now a real urgency.

This time pressure is compounded by the need to build reporting software and train national experts in time for the preparation of the first transparency reports in 2024.

In devising the “common reporting tables” and “common tabular formats” of the transparency framework, the key disputes centred around the flexibility that was assigned to developing countries and how to express this.

An early draft of the text, published on 9 November, offered three options for dealing with this issue, shown in the image below. The first option, supported by the US, EU and Australia, among others, would have entailed specific instructions for the use of flexibility being written into each of the reporting tables.

Another Q is how to flag the use of flexibility…

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) November 9, 2021

Do countries just leave a blank column?

Do they leave out that column/row altogether?

Can they “collapse” a table? [this might mean giving a subtotal without breakdown (?)]

Do they mark it with “FX”? pic.twitter.com/83fmXLCK9F

The last option, supported by the Least Developed Countries (LDC), African Group of Nations (AGN) and others, would have required countries to add the notation “FX”, meaning flexibility, in place of data they were not reporting.

The middle option was favoured by the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) – including China and India – the Arab Group, including Saudi Arabia, and Brazil.

This option gave a menu of flexibility choices, such as “not to display” certain “rows, columns and tables” that would contain no information – with this described by some insiders as China wanting to “delete” some of the transparency reports.

This disagreement – which was, ultimately, a matter of presentation – gave rise to some reporting of the negotiations that parties, such as China and Saudi Arabia, wanted to “thwart” progress towards a climate deal by refusing to accept transparency rules.

The reality was more nuanced, as Li Shuo, senior climate and energy policy officer at Greenpeace East Asia, told Carbon Brief:

“The haggles over trivial matters such as whether countries should report emissions in one column or two…reflect their broader grievance towards the COP26 political package. Finance has to be provided. Past promises need to be fulfilled.”

However, Li added that “taking the rulebook hostage is not the Paris spirit”, acknowledging that “carving out holes” in the regime would not align with a wider push for greater ambition.

Ultimately, countries needed to establish flexibility rules that would be appropriate for nations ranging from tiny Pacific islands with little technical capacity to superpowers responsible for large portions of global emissions.

When the final draft documents on transparency emerged as the conference drew to a close on Saturday, what had previously been a heavily bracketed – and, therefore, disputed – text appeared to be nearing a final conclusion.

Only a few brackets remained, all of them relating to how transparency reporting would account for Article 6 carbon markets – another incomplete aspect of the Paris rulebook that was yet to be decided at COP26.

Otherwise, the common reporting tables and tabular formats, report outlines and a training programme for expert reviewers were all essentially agreed.

“Proposals that some parties would not all use the same tables and formats for reporting are no longer included in the text,” Nathan Cogswell, a research associate at the World Resources Institute who had been tracking transparency negotiations closely, told Carbon Brief.

The text stated that countries requiring flexibility could “choose one or more” of a set of options, which include just using the “FX” notation, “collapsing” rows or columns where FX is used and collapsing entire tables reporting on less important greenhouse gases.

Cogswell told Carbon Brief that while “a number of flexibility approaches” are still included, in his view this “represents the compromise” after LMDCs originally pushed for rules that would mean some tables could be excluded altogether, and rows and columns could be deleted.

He said that he is still unclear about the implications of maintaining the ability to “collapse” and “expand” elements, adding that flexibility options may be built into the reporting software “in a way that would not impact the final presentation” of the reports.

The text also said that “interested” parties “may provide” information regarding loss and damage, a priority for developing countries that featured prominently in other areas of negotiations. (See: Loss and damage.)

When the final texts emerged, cementing the rules around transparency, the only last-minute changes related to Article 6, following the successful conclusion of those negotiations. For example, a table that had been a placeholder in case Article 6 talks collapsed was deleted.

“In Glasgow, parties completed the homework assignment they left themselves in 2018,” said Cogswell.

However, a briefing paper published by Chatham House examining the outcomes of COP26 remarked:

“The formal agreements reached at COP26 do not provide good grounds for optimism…that sufficient progress has been made on transparency and carbon markets.”

Common timeframes